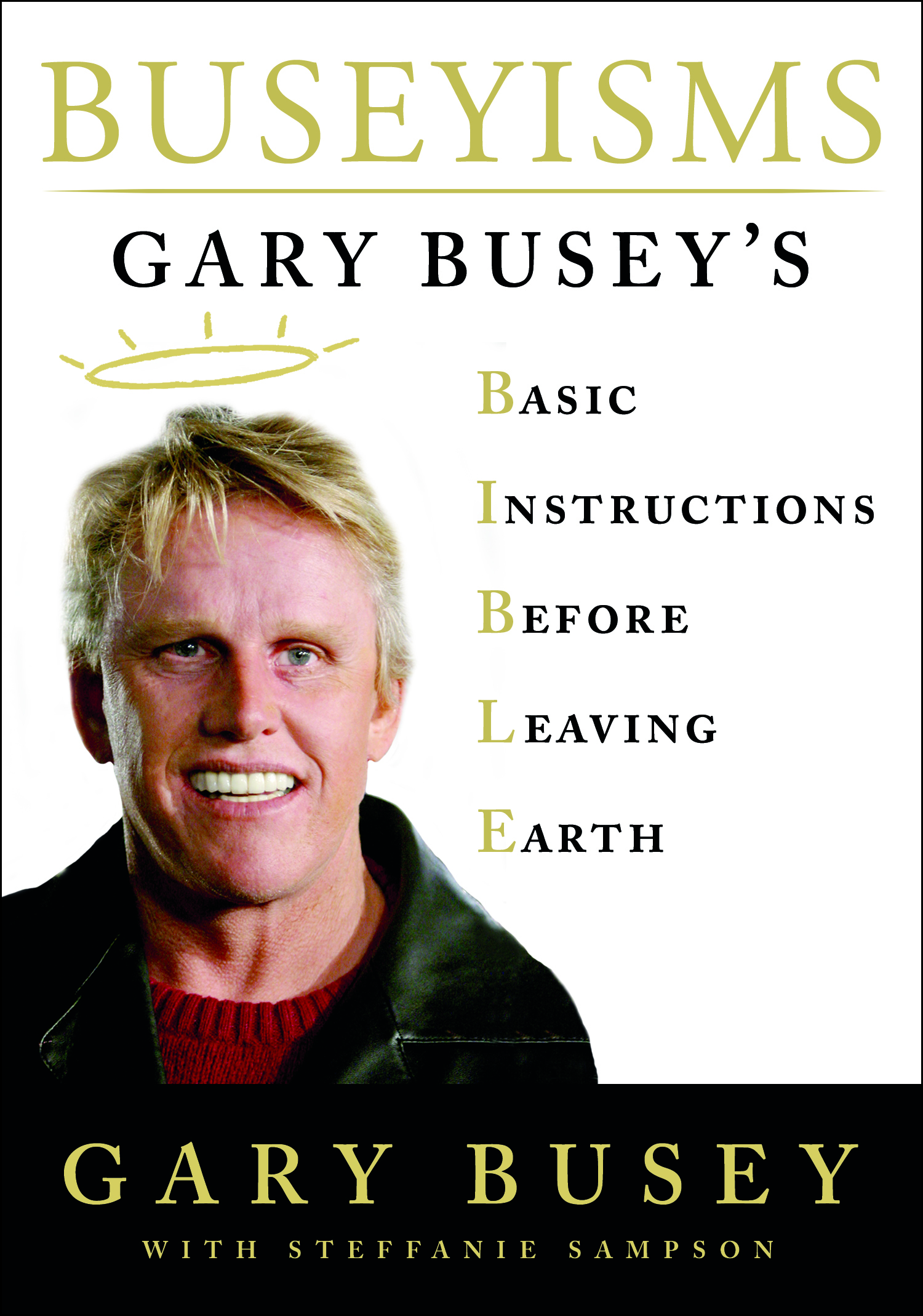

I am very excited to share with you an upcoming book release. Steffanie Sampson, a longtime member of the Unlocking Your Story workshop, has co-authored her husband Gary Busey's self-help memoir, Buseyisms. In the interview below, we chat about how the book came to be and her first experience through the traditional publishing process at Macmillan. I will be attending the LA book launch next Friday, September 7th and would love to see you there!

Steffanie Sampson is the co-author of the self-help memoir,Buseyisms, Gary Busey’s Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth (St. Martin's Press, September 2018). She is also an actress, stand-up comedian, hypnotherapist, and co-founder of the Busey Foundation For Children’s Kawasaki Disease. She recently won the So You Think You Can Roast competition held at the world famous Friar’s Club in New York City.

“Who am I, a genius, a crazy madman, to give advice? This is not advice. I am sharing the life lessons I learned while surviving the ups and downs of almost 50 years in Hollywood, a near fatal motorcycle accident, a drug overdose, two divorces, bankruptcy and cancer in the middle of my face. I may turn concepts you usually believe in upside down with my bizarre stories, but that comes with the dinner.

These are my life lessons, my B.I.B.L.E.—Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth.”

Karin Gutman: Oh my, it is almost here! How do you feel about your upcoming book release?

Steffanie Sampson: It is surreal. I remember when Gary and I met with Macmillan for the first time my editor said, ‘If we do this book, it will most probably be released in two years.’ I thought to myself, TWO YEARS?! Why so long? ... That day seems like yesterday.

KG: Can you share about the book and how it came to be?

SS: For years, Gary has been constructing Buseyisms. Those are unique word-phrases he makes to create a deeper, more dimensional meaning for words using the letters that spell them.

For example, FART (a fan favorite): Feeling A Rectal Transmission.

Another popular one (and one of his longest) is for the word RELATIONSHIP: Really Exciting Love Affair Turns Into Overwhelming Nightmare Sobriety Hangs In Peril.

For some time, Gary and I wanted to release a book of his Buseyisms, but we weren’t sure how to formulate it. At first we thought of a coffee table book with just illustrations, but no one seemed interested in publishing that. I brought the idea to you, my amazing writing coach Karin Gutman, and together we brainstormed and finally figured out the perfect hook: to tell the stories of Gary’s colorful life through his Buseyisms, sharing the life lessons he has learned along the way.

Once we figured out the format, everything happened to fall into place as if it was divinely guided. One morning we were in the green room at Good Day New York promoting a play that Gary was in, and we ran into an acquaintance of ours, Hayes Grier, who was also doing Good Day New York to promote a new book he wrote. When he introduced us to his publicist, I told her that we were writing a book and asked whom I could contact at Macmillan. I sent an email and got a response within a day asking for a proposal. Since it was just an idea formulating in my mind, I spent the next few days writing a proposal, and consulting with you again, which helped me immensely. After I sent the material to Macmillan, we had a meeting with them, and they offered us a book deal. At the meeting, I told our future editor we were open to all possibilities regarding a ghostwriter, but he wanted me to write it. And now two years later, our book is in the physical form.

KG: As the ghostwriter of your husband’s story, what was your process in getting the story out on the page?

SS: I really wanted the book to be very readable and fun. I wanted each chapter to be a complete story that could stand alone and be read at any time, similar to the book, Chicken Soup For The Soul. I put myself in the place of the reader and dissected Gary’s life to help me select 50 of his most interesting stories. Then I asked Gary to talk about each story in detail while I recorded him. After a lot of editing, because Gary likes to talk, I made each story roughly 4-5 pages long. We were also required to include 35-50 pictures in the book, so while I was writing the stories, I was also working with various photographers and studios licensing pictures that were cohesive to each story.

KG: What was the most challenging aspect of writing this book?

SS: The most challenging aspect of writing the book was getting Gary to go deep. There were some things in his life that he didn’t like to talk about, and I really had to explain to him the value of getting everything out on the page. Gary tends to have a real positive outlook and doesn’t like to wallow in the past. I explained that telling stories about what happened in his life was not wallowing in the past and could be very inspirational for people. I mean, Gary survived physical abuse by his father, substance abuse, a near fatal motorcycle accident, cancer in the middle of his face, a drug overdose, bankruptcy, and so much more… there’s a lot that people can relate to. It took me a while to get him on board, but once he understood that telling his stories could help other people, then the writing really flowed.

KG: What is the most rewarding aspect?

SS: It’s hard to choose the most rewarding aspect. I think having a finished product in hardcover and people getting to know the real Gary - and not the Gary that the media has portrayed - is the most rewarding thing for me. In the ten years I’ve been with Gary, it's been frustrating to see people assume he’s a certain way that he isn’t. Most people assume he’s a crazy nut-bag, but really he’s a very deep, spiritual person. I’m very excited for people to learn the truth about Gary.

KG: How the heck did you finish by your deadline, as a mother of a young child to boot!? What was your writing process like?

SS: I really have no idea how I did it. It’s almost as if the book wrote itself and I was just a channel. During the ten months that I wrote the book, I was pulled in so many different directions by Gary, our son Luke, and everyday life, but I kept my focus strong. I knew I had a deadline and I wrote every minute I could to make the deadline. I wrote and shared many of the early chapter drafts in your Unlocking Your Story workshop. I would take Luke to school, then lock myself in a room all day long until it was time to pick Luke up from school. I divided up the ten months by chapter and made sure I kept on schedule.

KG: I remember speaking to you early on about all the UNKNOWNS working with a publisher and editor. Can you describe the process and share some details, now that you’re on the other side?

SS: After we signed the book deal, I spoke to our editor about his vision, then I told him mine, and then strangely enough, I was left alone pretty much until the deadline. At one point about four months into it, my editor wanted to see some chapters to make sure I was on the right path. I sent him what I had completed, and surprisingly he sent me a simple note saying he liked what he saw and that he didn’t need to see anymore until the book was due. Once I turned the book in, he read it, wrote minimal notes, cut two chapters (I ended up writing 52 chapters), and that was that.

KG: I know you considered having an agent represent the book. Why did you choose NOT to have an agent and do you think that served you?

I considered having an agent in the beginning because I wanted to make sure we had a good deal. After negotiating with Macmillan, and speaking to some people in the industry, I realized that Macmillan’s deal wasn’t going to change whether I had an agent or not. They were pretty definite. I’d already done the bulk of the work getting the deal, and at that point having an agent wasn’t going to be beneficial at all, so I opted out. My experience with Macmillan has been positive thus far, and everything we’ve asked for we’ve gotten, so I think I made the right decision.

KG: What kind of support are you getting from the publisher on the promotion of it? Are they relying on Gary’s celebrity and personal publicist to generate promotional opportunities?

SS: At the moment Gary does not have a personal publicist, so we are completely relying on publicity provided by Macmillan. It may be too early to comment on publicity, but it seems like they are presenting us with some good opportunities.

KG: As the ghostwriter, what is your role now that the book is out? Will you continue to be behind the scenes?

SS: I’d like to say that it was very important for me to have my name on the book as a co-author. I was really instrumental getting the book deal, and putting it together with Gary, so I wanted to be recognized. That said, I really don’t know what my role will be. I will make myself available to the publishers, and to Gary, if they need me for anything.

KG: Does this book make you want to write your own story one day?

SS: I think someday I will definitely write my own book. It doesn’t feel like it will be any time in the near future. I would be open to ghostwriting another book if the price is right and the subject is pleasing to me.

KG: What does Gary think of the book? Is he happy with it?

SS: Gary is thrilled with how the book turned out, thank God!

Meet Gary Busey + Steffanie Sampson

~ Upcoming Readings & Signings ~

Tuesday, Sept. 4th @ 6 PM EST

Bookends

East Ridgewood Avenue Center, 211 E Ridgewood Ave, Ridgewood, NJ 07450

Wednesday, Sept. 5th @ 7 PM

The Book Revue

313 New York Ave, Huntington, NY 11743

Thursday, Sept. 6th@ 6 PM - 8 PM EST

FRIARS CLUB BOOK WARMING

with James “Murr” Murray from Impractical Jokers

3205, 57 E 55th St, 2nd Floor, NYC 10022

Friday, Sept. 7th @ 7 PM PST

Barnes & Noble @ The Grove

189 The Grove Drive Suite K30

Los Angeles 90036

Event link